Kelly Rose

Editor

Kelly Rose

Editor

Paul Bussey, associate - technical, Scott Brownrigg, examines the ramifications of the Construction Design and Management (CDM) Regulations 2015.

The 6th April saw the new Construction Design and Management (CDM) Regulations 2015 come into effect, following a lengthy five year evaluation of the 2007 Regulations. Whilst the new regulations will have significant implications for all those involved in construction, the intention is simple - to prevent the ill health or death of construction and maintenance operatives, whilst also allowing for the delivery of good design.

The outcome of the process is a re-focusing on the team approach, underpinned by the intentions of the overarching 1974 Health and Safety at Work Act, and aimed at proportionality, reasonable foreseeability and practicability. This, in conjunction with the 1999 Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations where the concept of 'suitable and sufficient assessment of risk' was reinforced, set the landscape within which the 1994 and 2007 CDM Regulations sat.

Whilst originally intended for process industries, where absolute duties to eliminate and reduce risk could be applied, the application of these regulations to design tasks has been much more complex. This has, in some cases, led to confusion and unintentional misinterpretation by some duty holders lacking design training, who have expected designers to ‘design out’ all risk from their concept designs. The implementation of such expectations can stifle innovative design and inhibit designers from establishing acceptable or tolerable levels of risk within the constraints of cost, time, quality, aesthetics, and contextual expectations.

This disconnect has caused frustration within the industry and has highlighted the need to balance and co-ordinate health and safety prevention principles and innovative design right from the start of the design stage. A return to the original intentions of the ‘planning supervisor’ has been necessary. The new principal designer role addresses these issues and, as required by the 1992 EU Directive, provides a 'Health and Safety Coordinator of the Project Preparation phase embedded within the existing design team and in control of preparing and modifying [actual] designs'.

The new principal designer function is intended to integrate health and safety considerations into the design process in a proportionate and practicable manner, to avoid and minimise risk so far as reasonably practicable and to provide a design which not only meets the client brief but sets and identifies a tolerable level of risk for the client to fund, the contractor to build, and the user to operate.

In order to facilitate such a position it is essential for the entire project team to work together as a cohesive unit, without the fear of blame or civil or criminal prosecution in the event of a failure or accident. Unfortunately history shows us that, in carrying out complex and sophisticated tasks, it is almost inevitable that some accidents will occur, primarily due to human behaviour and unforeseeable events, even though we have made huge progress to reduce their occurrences and impact. The aspiration to simply 'design out' risk has arguably reached its effective limits. There is now a need to identify a more sophisticated, and more intuitive, process of risk identification, analysis and identification with the end result of reducing risk.

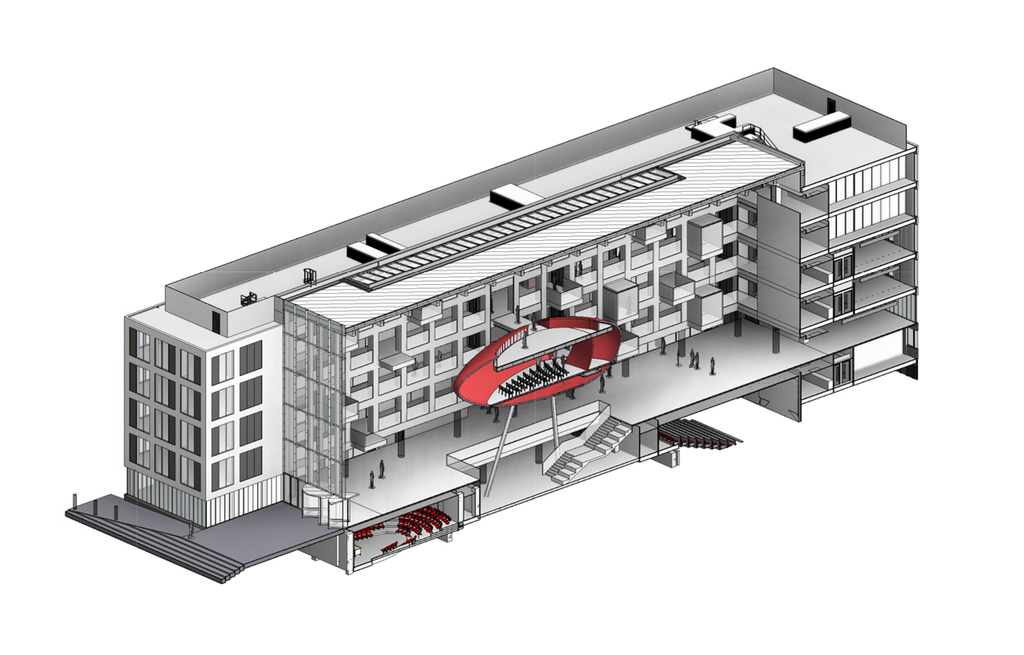

Design is a highly visual process requiring the production of images to assimilate the contributions of team members into one cohesive entity. The integration of safety into design is no different. By identifying potential harm visually and directly on drawings, issues can be discussed in team forums, managed to a tolerable level within the constraints of the design intent and embedded into the normal design process. The alternative narrative or numerical method cannot communicate in the same direct, transparent and collaborative way.

The immediate future requires the industry to re-organise itself during the project preparation (design) phases to embrace risk and identify levels of tolerability. At the other end of the process, during the project execution (construction) phase, small and medium size contractors need to embed these regulations into their approach. The professional institutions and trade associations need to take ownership of the skills, knowledge and experience of their own members by the introduction of training and lifetime learning processes.

This process will require a level of integrated professionalism from all construction industry participants, including the Health and Safety Executive inspectors and prosecution officers, public indemnity insurance lawyers and other judicial members of the legal system. Case law should not be the only means to test whether or not these interpretations of the regulations are adequate.

The new CDM landscape should enable design innovation and excellence whilst facilitating the inclusion of safe methods of working on every construction project; an outcome to which we can all aspire.

For more information visit www.ribabookshops.com/item/cdm-2015-a-practical-guide-for-architects-and-designers/84369/

77 Endell Street

London

WC2H 9DZ

UNITED KINGDOM

020 7240 7766